Beate Kubitz: Rural and Low-Density Bus Routes

Running rural buses is a particularly knotty problem. With low-density populations and small budgets, authorities have had to make very hard choices of which services to subsidise. Do they prop up as many legacy services as possible (even with a reduced number of services) or do they rethink?

The practical problem belies a fundamental question: ‘What is an equitable way of running rural transport?’ In effect, is it fairer for authorities to retain a skeleton of regular services along corridors or to spread out less regular services over a broader area?

It’s a problem recognised in transport planning as frequency vs coverage. It’s also problematic in cities too, but in rural areas where populations are much less dense and services are even more strung out it’s much harder to solve. Corridors of services run with regularity are often only accessible to a minority of people, leaving people in smaller hamlets impossible distances from bus stops. A meandering route may pass closer to more people but will also inflate the journey times and reduce frequency (without additional resources).

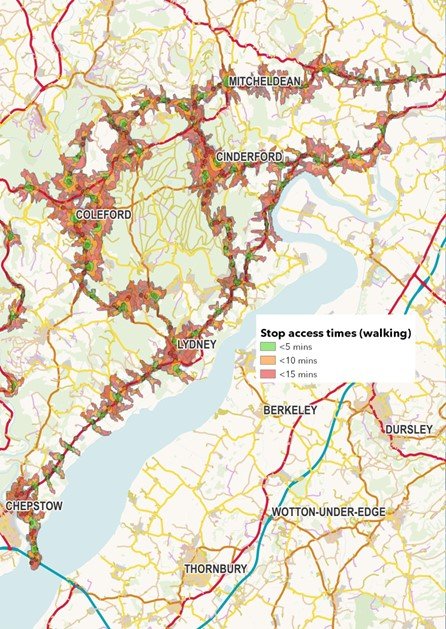

In an area with defined corridors, rural bus services generally follow the main routes. For instance, the Forest of Dean has an excellent and frequent service between Coleford and Gloucester run by Stagecoach on a commercial basis. It is augmented by other routes, however, these also follow certain corridors. A coverage analysis looking at the distances people live from bus stops shows public transport is too far to be accessible to the majority of the population. Both people and destinations off the corridor are not served.

When it comes to subsidising services, there are some quite tricky questions about the equity of who is served by rural buses – both spatially and by demographic.

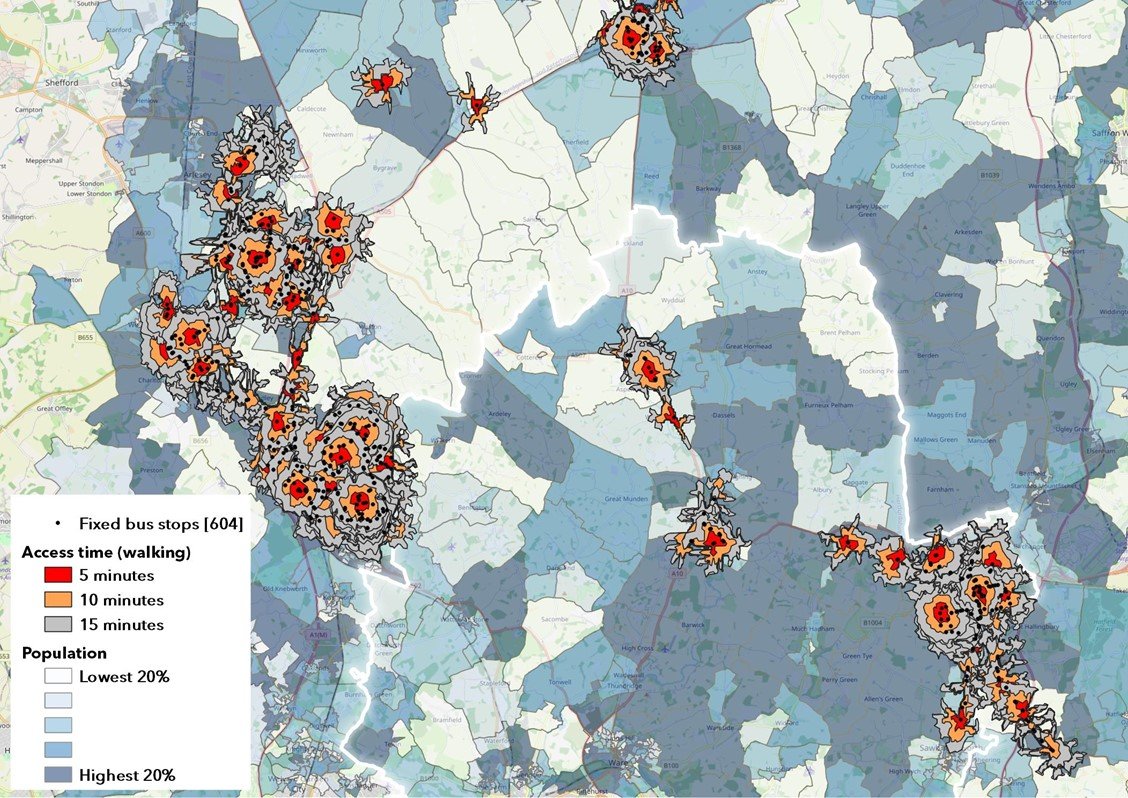

The spatial question is about serving some places but not others. A bus route along a corridor will not reach all the people living in the area (in the diagram of North East Hertfordshire below around 40,000 people do not have access to a bus with a regular hourly or better service).

Then there are the times at which the buses run. Should they favour shoppers on market day, college students or workers commuting to neighbouring towns? How should the authority interpret the concept of ‘socially necessary’ services, particularly as the modal shift is required to meet emissions and other environmental goals. The costs of running rural routes (even quite infrequently) are high and the subsidy per passenger can be eye-watering, choosing the routes, the timetable and who to favour is almost impossible.

Local authorities trying to serve more places and a broad range of people – particularly where journey origins and destinations can be quite distributed (rather than conveniently along corridors) are trialling on-demand bus services to cover much wider areas.

DRT services can increase the number of people who have access to a bus quite substantially. In the example above we know that the new DRT service covers an additional 30,000 people with its 4 buses. In addition, they are available 12 hours a day, meaning they don’t favour one group over another.

This gives rise to some interesting observations about how we should measure the success of DRT. If previously only 20% of people living in the rural community lived within walking distance of fixed routes, and that is increased to 72% living within walking distance of virtual bus stops by adding DRT, how should we include this in the scheme’s evaluation? The detailed data provided by DRT makes it easy to estimate the percentage of the population using it and the distribution between those who have had some access to buses previously and (using spatial analysis) those who have only newly had access with the arrival of the DRT.

Things can’t continue as they are, with rural communities increasingly disconnected. DRT is an important tool for rethinking routes and looking at how best to deliver value to everyone within an area.

Beate Kubitz - Researcher & Consultant Beate Kubitz Associates Ltd